1006 Morton Street

Baltimore, MD 21201

410.576.9131 | RW1haWw=

May 29 2008

Lucky's Warehouse: A Sustainable Adaptive Reuse in South Baltimore

?The first step in sustainability is to reuse an existing building.? ? Michael Furbish, developer of Lucky?s Warehouse

Lucky?s Warehouse is a sustainable adaptive-reuse of an industrial space built in the Brooklyn / Curtis Bay area of South Baltimore. The warehouse was originally built to house a millwork shop and was later converted into a storage facility. Despite falling into disrepair during the last century, the current incarnation of the 1920?s warehouse has been remodeled to accommodate roughly 18,000 sf of open plan office space over three floors. Also added to the aged brick warehouse are simple, durable sustainable strategies which provide healthy, affordable, energy efficient, and environmentally friendly lease space in an area of Baltimore that has seen much physical, cultural and economic erosion over the years. Out of the chaos of roads, rail tracks, waterways, parks, and structures that is Brooklyn Maryland, the renovation of Lucky?s Warehouse integrates systems to the benefit of occupants and the environment. And in the future, the project may provide a design philosophy to direct similar adaptive reuse projects seeking to achieve sustainability on economic, environmental and social terms.

Lucky?s Warehouse was developed and planned by sustainable consultant and high performance building systems provider Michael Furbish of Furbish Company. Architect on the project was Peter Fillat and the advanced building systems were designed by EarthStar Energy Systems of Waynesboro VA. The project is complete with exception of ongoing tests and adjustments being made to the high performance building systems.

In an interview with Mr. Furbish, he comments that ?the first step in sustainability is to reuse an existing building,? and went on to explain that his basic philosophy was to rely on simple effective ways of delivering a high performance sustainable building. It was that reasoning that led Furbish Company to choose simple integrated solutions to the problems of energy generation, thermal conditioning, and lighting of the building. For instance, in lieu of a high profile photovoltaic (solar electric) system, Furbish selected a solar thermal system as the best way of generating thermal energy for the building. Furbish went on to argue that solar thermal gives ?more bang for the buck? than PV and provided better options for conditioning the building.

In an interview with Mr. Furbish, he comments that ?the first step in sustainability is to reuse an existing building,? and went on to explain that his basic philosophy was to rely on simple effective ways of delivering a high performance sustainable building. It was that reasoning that led Furbish Company to choose simple integrated solutions to the problems of energy generation, thermal conditioning, and lighting of the building. For instance, in lieu of a high profile photovoltaic (solar electric) system, Furbish selected a solar thermal system as the best way of generating thermal energy for the building. Furbish went on to argue that solar thermal gives ?more bang for the buck? than PV and provided better options for conditioning the building.

The project did not choose to seek LEED certification at least partly because Mr. Furbish?s intuitive definition of sustainability and the project's dedication to effective and practical solutions make "chasing points" secondary to achieving a truly high performance building design. Furbish acknowledges that the building does not meet USGBC requirements. But he does feel, and I agree on this point, that sustainability is a broad metric and that the decisions made during the design and construction of Lucky?s capture the spirit of sustainability (even as defined by the USGBC). It succeeds on all the most important points in my mind and in some ways supersedes the point based metric of LEED in favor of a more general definition of sustainability.

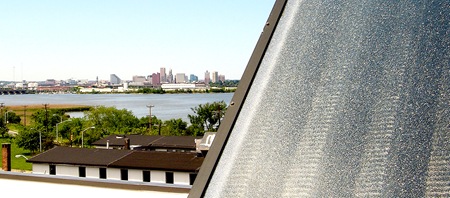

Location, location, location? Lucky?s Warehouse is a terrific example of adaptive reuse in an urban setting. The building, previously unoccupied, lies just ¼ mile to I-895, ½ mile to I-95 and 3 miles to downtown Baltimore. The area is previously developed and already has infrastructure connected such as water, gas, electricity and transportation. The site accesses public transportation, bodies of water, and is near a commuter rail line. From an sustainability standpoint, Lucky?s surely meets the spirit of LEED?s Sustainable Sites credits and likely exceeds them in some instances.

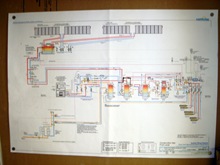

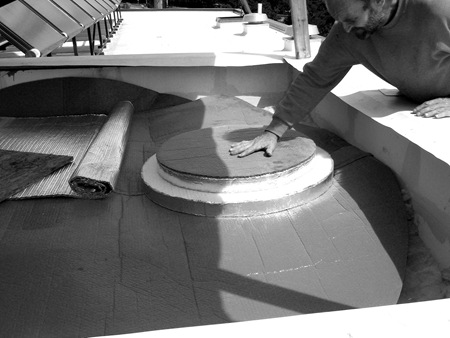

Sustainable design strategies for Lucky?s include reuse of building shell, aggressive heating and cooling, well insulated envelope, designing for natural light, and advanced energy use monitoring system. The building envelope uses 7? rigid polyiso insulation on the roof for an R-value of 40. 15-18? masonry exterior walls provide for high thermal mass along the perimeter. The building is heated using a radiant hydronic system imbedded into the floor plates between the existing wooden flooring and a 2? polished concrete topping slab that also serves as the finished floor material. Cooling is provided by both the radiant flooring system and a forced air unit. Heating and cooling energy is provided through a simple integrated system of solar thermal panels, an open loop ground source heat pump, a series of heat pumps to extract heat from the water loops, and an energy recovery ventilator.

Primary heating energy is provided by the (28) 4?x10? roof mounted solar thermal panels connected to a 1,500 gallon storage tank. (roof mounted as well). Additional heating, during cloudy or winter periods, comes from a heat pump fed off the open loop ground source heat pump (GSHP). Primary cooling is done using the radiant flooring system. The system is set to use >=71°F water directly from the GSHP if possible. The radiant system is never allowed to reach dew point to avoid condensate build up. Supplemental cooling is provided by a water to air heat pump that feeds a forced air system throughout the building. ASHRAE requirements for ventilation are met alongside increased energy efficiency goals through the use of an energy recovery ventilator.

It is worth noting that because of the building?s location, the developer cited no major regulatory problems when applying for the ?open loop ground source heat pump? system.

The Lucky's Warehouse project is a good example of how an integrated systems design approach, also called total building performance / whole building design, can leverage the strengths of several systems to create an extremely efficient, sustainable building. Still, we have not mentioned the final component, and perhaps the most important piece of the ongoing lifecycle of this building, the occupant. Their engagement with the building and building systems, or lack thereof, will ultimately decide Lucky's sustainability. In order to encourage interaction between the tenants and the building systems, the developers have installed utility metering systems that display real-time usage for different areas of the building. Mr. Furbish hopes that acknowledgement of the relationship between occupants and building systems, and specific information about the performance of the building, will allow users to become truly sustainable by modifing both the building and their own behaviors.

This post written after interviews with Furbish Company founder Michael Furbish and building systems specialist James Uhrich.

For more information on the project please visit Furbish Company website.

Building Stats:

Envelope

- 7? Polyiso (R-40) Roof Insulation

- 15-18? Masonry Walls

- Radiant floors composed of existing wood flooring + hydronic system + 2? polished concrete topping slab

- Insulated Low-E High Performance Glazing

Systems

- Solar Thermal System

- Open Loop Ground Source Heat Pump

- Energy Recovery Ventilator

- Radiant Heating / Radiant + Forced Air Cooling

- Energy Consumption Monitors

Indoor Environment

- Natural Light

- Polished Concrete Floors

- No-VOC / Low-VOC finishes

Recent Posts

Reimagining Harborplace to Create Space for Both Private Development and Expanded Public Space » Lawyer's Mall Reconstruction Progress » Confronting the Conventions of Customary Practice » Reconceived Facades: New Roles for Old Buildings » Ivy Bookshop Opens for Business! »

Categories

Yellow Balloon Baltimore » Products + Technology » Industry + Practice » Other » Architecture »

Links

Organizations

- USGBC Baltimore Regional Chapter »

- AIA - American Institute of Architects »

- USGBC »

- The Walters Art Museum »

- Green-e »

- Center for Building Performance and Diagnostics (CMU) »

- Green Globes »

- Prefab Lab (UT) »

- Center for Sustainable Development (UT) »

- Architecture 2030 »

- Bioneers »

- Street Films »

- FreeCycle »

- Chesapeake Bay Foundation »

- Archinect »

- BD Online - The Architects Website »

- National Wildlife Foundation »

- Natural Resources Defense Council »

- Overbrook Foundation »

- Merck Family Foundation »

- Ecology Center »

- New Building Institute »

- Neighborhood Design Center »

- The Leonardo Academy »

- ZigerSnead Architects LLP »

- The Rocky Mountain Institute »

- Urban Habitats »

- ACORE - American Council on Renewable Energy »

- Parks and People Foundation of Baltimore »

- Open Society Institute of Baltimore »

- Natural Capital Institute »

- Passive House US »

- Svanen Miljomark »

- Green Restaurant Association »

- Rocky Mountain Institute »

- Green Exhibits »

- Green Roundtable »

- John Elkington - SustainAbility »

- SustainAbility »

- Building America »

- Endangered Species Program - Fish and Wildlife Service »

- Congress for the New Urbanism »

- Urban Land Institute »

- Cool Roof Rating Council »

- Montgomery County (MD) Public Schools Green Building Program »

- National Institute of Standards and Technology Software »

- Scientific Certification Systems »

- Community Greens »

- CBECS »

- CASE - Center for Architecture Science and Ecology »

Interesting Sites

- The Ecologist »

- Treehugger »

- Grist »

- WIRED »

- Planet Architecture »

- MiljoBloggAktuellt - Environmental News Blog (Swedish »

- Sustainable Design Update »

- Eikongraphia »

- World Architecture News »

- The Cool Hunter »

- Design Center »

- ZEDfactory »

- Architen Landrell Associates Ltd. »

- Environmental Graffiti »

- businessGreen »

- Best Green Blogs Directory »

- Groovy Green »

- EcoGeek »

- Urban Ecology »

- Locus Architecture »

- Urbanite »

- A Daily Dose of Architecture »

- Adaptive Reuse »

- Audacious Ideas »

- Big Green Me »

- NOTCOT »

- Sustainable Baltimore »

- Thoughts on Global Warming »

- Green Maven »

- WorldChanging »

- Go For Change »

- Building Green »

- Home Energy Magazine »

- Home Energy Blog »

- FEMA Map Service- Federal Emergency Management Association »

- Architectural Graphic Standards »

- E-Wire »

- Post Carbon Cities »

- Alt Dot Energy »

- Whole Building Design Guide »

- B'more Green »

- EJP: Environmental Justice Partnership »

- Baltidome »

- OneOffMag »

June 5th, 2008 at 7:35 AM

Green Warehouses: Corporations Meet Sustainability Challenge «

[...] Warehouse project in Baltimore is the subject of a well-explained and profusely illustrated case study at Greenline, and many other similar projects are being developed throughout the [...]